Uncategorized

Growing Pains, Part 3: Jumping ship

Published

5 years agoon

Posted By

Outlaw Partners

As urban centers swell, waves of city dwellers are paddling for higher ground

By Michael Somerby and Bay Stephens EBS DIGITAL & LOCAL EDITORS

BIG SKY – By the time Congressman Greg Gianforte moved to Bozeman in 1995, he’d already sold four companies, most notably a $10 million sale of a banking management software to McAfee Associates, a global computer security software company.

Enticed by bounties of nature surrounding the town, which held a population of about 25,000 at the time, Gianforte was also on a mission: prove business was no longer limited by geographic restrictions in the internet age, reducing overhead costs and headaches associated with living in major metropolitan markets.

In 1997, Gianforte and his wife Susan founded RightNow Technologies, a customer-relationship management software service. By 2004, when RightNow went public, the company employed more than 1,000 individuals in offices in the U.K., Asia and Australia, and in 2011, Oracle Corporation acquired the company for $1.5 billion.

To say RightNow Technologies was successful is an understatement. The venture not only proved Gianforte’s hunch that the Internet could conquer distance between the nation’s premiere business cities, it also created an ecosystem for fellow tech-minded executives and their startups in Bozeman.

Similar stories are playing out across the Intermountain West.

“You have entrepreneurs who are realizing they don’t need to be in Silicon Valley or L.A. or New York or Chicago anymore, especially in the tech industry,” said Mike Magrans, a partner at Ernst and Young, the New York City-based global professional service firm consults investors, owners, and operators in the real estate and hospitality industry.

“They can work in Salt Lake or Denver … or Jackson [or] Bozeman because they’re starting to be able to attract talent, and wherever you’re able to attract talent, or wherever you have access to higher education, like Montana State, you’re going to be able to create companies.”

Along with startups, the Intermountain West is attracting remote workers who can telecommute to their offices in major cities. Magrans said he’s seeing people opting for the quality of life that mountain locales offer over the bustling cities, a trend he attributed to the strong economy, current technology and how millennials are capitalizing on the flexibility afforded by that technology.

“People are starting to work remotely and be very efficient and productive by being mobile,” Magrans said. “… And as long as you have great Internet access, why not be in the mountains?”

According to Mark Haggerty, an economist at the Bozeman-based research institute Headwaters Economics, Bozeman’s revolution began with RightNow Technologies. Gianforte, Haggerty says, built a “…spinoff tech cluster standing on its own two legs.”

A Headwaters Economics study released in January of 2019 highlights the uptick in migration to “recreation counties,” defined by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (USDA ERS) by three necessary components: “the share of employment in entertainment and recreation, accommodations, eating and drinking places, and real estate; the share of personal income from these same categories; and the share of vacant housing units … for seasonal use.”

The occurrence is especially prominent in micropolitan communities, classified by the ERS as having between 10,000 to 50,000 residents with at least one urbanized area, and rural communities, which have fewer than 10,000 residents.

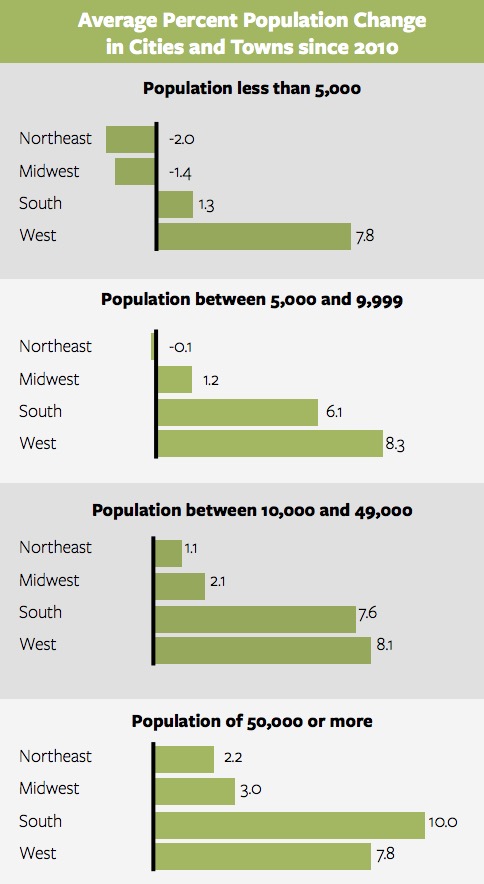

Ignoring recreation, metropolitan communities received the lion’s share of domestic immigration between 2010 and 2016, but when recreation is factored in, a different story is told.

Between 2010 and 2016, a period of recovery “from the end of the Great Recession,” non-recreation metropolitan counties saw an average net migration rate of 12.5 people per 1,000 residents, but their recreation counterparts grew by 45.9 per 1,000. Non-recreation micropolitan counties lost an average of 15.6 per 1,000 residents—conversely, recreation micropolitan counties grew by an average of 21.6 people per 1,000. When non-recreation rural counties lost an average of 19.9 per 1,000 residents, recreation rural counties gained an average of 1.3 per 1,000.

Bozeman, nestled squarely in prime country for skiing, mountain biking, fishing, hunting and other outdoor pursuits, fits the criterion of an urbanized area within a recreation county. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, its 2017 population was about 46,500 residents, teetering on the metro and micropolitan fault lines. According to a 2018 Bureau report, Bozeman was the fastest growing micropolitan area in the nation.

The same report estimated Bozeman’s growth rate at 3.6 percent between 2016 and 2017, which if sustained would double the city’s population in two decades. By next year, the city is expected to reach 50,000 residents, according to a report commissioned by the city of Bozeman.

Haggerty cites a “golden triangle” effect when considering Bozeman’s staggering and unprecedented growth.

“Bozeman has three key components—a national park [Yellowstone], an efficient airport with direct access to larger markets and a highly educated workforce supplied by MSU.”

On April 11, Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport authorities as well as Gallatin County Commissioner Scott McFarlane and others broke ground on a 70,000-square-foot concourse expansion project.

The last expansion took place in 2009, when the airport serviced a meager 700,000 annual passengers. In 2019, estimates have passengers serviced at 1.5 million, a reflection of the hordes of tourists seeking recreation in the surrounding mountains and at Yellowstone National Park.

In 2018, the park had 4.1 million guests, up from 3.07 million in 2008, according to official park visitation figures.

From a financial perspective, Magrans said capital is flowing to “tertiary” cities like Bozeman that have small populations and far higher real estate returns because they are riskier investments, albeit they are more prone to economic downturns than major markets like New York City, Chicago or San Francisco.

“Right now, as an investor, I can get a heck of a lot more return on my capital by investing in a tertiary city piece of real estate [than in a major metropolitan city],” Magrans said.

He likened today’s migration trends to those of the ‘70s and ‘80s when people were moving to the suburbs, adding that the development of technology acts as the driver of current migration patterns.

“It is remarkable, because in 2007 we didn’t have an iPhone, in 2007 we didn’t have Uber. We didn’t have all these apps at our fingertips to provide you services and enable you to work more remotely,” Magrans said. “And that was only 11 years ago.”

And technology isn’t the only factor at work. Places like Bozeman offer high quality of life at a much cheaper rate than the big city.

According to the Cost of Living Index published by the Council for Community and Economic Research, a city-to-city cost comparison recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and CNN Money, an individual moving from Bozeman to San Francisco, one of the nation’s most expensive cities, would need an 87 percent increase in salary to maintain the same level of lifestyle. Conversely, a person in San Francisco can take a 46-percent pay cut and sustain the same economic lifestyle in Bozeman.

In relative terms, a worker living in San Francisco making $100,000 annually could maintain the same level of lifestyle on $54,000 a year.

“I would argue that as long as that differential exists, you’re not going to see a big slowdown here,” said Bozeman-based real estate and property consultant Bruce Burger at an event called Whither Gallatin hosted by Future West in Bozeman in early April. “… It’s not a 10 percent difference. It’s a 40 percent difference.”

Burger’s presentation at the Whither Gallatin event spoke to the interconnectedness of Bozeman and Big Sky, calling the latter Bozeman’s “x-factor.”

“You can’t talk about Bozeman without talking about Big Sky,” Burger said. “It is an unseen force. [Big Sky is] generating hundreds of millions of dollars in direct and indirect economic investment in the Bozeman economy.”

Burger said that as many as 2,000 workers each day commute from Bozeman to Big Sky, which would represent 5 percent of the adult population of Bozeman. Employees and workers, such as those building the ultra-luxury hotel Montage Big Sky in Spanish Peaks, can’t afford to live in Big Sky, spending their wages on living expenses in Bozeman. With an alleged billion dollars of improvements taking place in Big Sky, Bozeman is reaping the benefits.

According to Haggerty, there’s an economic theory that businesses will always look to spread out the cost of business. Yet, he said, what Gallatin County’s witnessing is not diffusion but concentration due to a premium placed on being around other “energetic and creative people.”

As a result, Bozeman, along with other Gallatin County communities will experience increasing strain from snowballing immigration.

“The problem is, too much growth brings the same urban problems people left in the first place,” Haggerty said. “Then it becomes ‘be careful what you wished for.’”

The Outlaw Partners is a creative marketing, media and events company based in Big Sky, Montana.

Upcoming Events

april, 2024

Event Type :

All

All

Arts

Education

Music

Other

Sports

Event Details

Children turning 5 on or before 9/10/2024:

more

Event Details

Children turning 5 on or before

9/10/2024: Kindergarten

enrollment for the 2024-2025 school year can be completed by following the

registration process now.

Children

born on or after September 11, 2019: 4K enrollment is now open for

families that have a 4-year-old they would like to enroll in our program for

the 2023-2024 school year. Please complete the 4K Interest Form to

express your interest. Completing this form does not guarantee enrollment into

the 4K program. Enrollment is capped at twenty 4-year-olds currently

residing within Big Sky School District boundary full time and will be

determined by birth date in calendar order of those born on or after September

11, 2018. Interest form closes on May 30th.

Enrollment now is critical for fall preparations. Thank you!

Time

February 26 (Monday) - April 21 (Sunday)

Event Details

Saturday, March 23rd 6:00-8:00pm We will combine the heart-opening powers of cacao with the transcendental powers of breathwork and sound. Together, these practices will give us the opportunity for a deep

more

Event Details

Saturday, March 23rd 6:00-8:00pm

Time

March 23 (Saturday) 6:00 pm - April 23 (Tuesday) 8:00 pm

Location

Santosha Wellness Center

169 Snowy Mountain Circle

Event Details

We all are familiar with using a limited palette, but do you use one? Do you know how to use a

more

Event Details

We all are familiar with using a limited palette, but do you use one? Do you know how to use a limited palette to create different color combinations? Are you tired of carrying around 15-20 different tubes when you paint plein air? Have you ever wanted to create a certain “mood” in a painting but failed? Do you create a lot of mud? Do you struggle to achieve color harmony? All these problems are addressed in John’s workbook in clear and concise language!

Based on the bestselling “Limited Palatte, Unlimited Color” workbook written by John Pototschnik, the workshop is run by Maggie Shane and Annie McCoy, accomplished landscape (acrylic) and plein air (oil) artists,exhibitors at the Big Sky Artists’ Studio & Gallery and members of the Big Sky Artists Collective.

Each student will receive a copy of “Limited Palette, Unlimited Color” to keep and take home to continue your limited palette journey. We will show you how to use the color wheel and mix your own clean mixtures to successfully create a mood for your paintings.

Each day, we will create a different limited palette color chart and paint a version of a simple landscape using John’s directives. You will then be able to go home and paint more schemes using the book for guidance.

Workshop is open to painters (oil or acrylic) of any level although students must have some basic knowledge of the medium he or she uses. Students will be provided the book ($92 value), color wheel, value scale and canvas papers to complete the daily exercises.

Sundays, April 14, 21 and 28, 2024

Noon until 6PM.

$170.

Time

14 (Sunday) 12:00 pm - 28 (Sunday) 6:00 pm

Event Details

Everyone is invited to join us in celebrating 2 years of arts education in the BASE Art Studio with us! Take a tour

Event Details

Everyone is invited to join us in celebrating 2 years of arts education in the BASE Art Studio with us! Take a tour of the studio, meet our instructors, and meet other artists of all levels in our community. We’ll be getting creative and you’ll have the chance to make your very own artful button pin.

Stick around for our Volunteer Appreciation and Social beginning at 6:30 p.m.!

Time

(Thursday) 5:30 pm - 6:30 pm

Location

BASE

285 Simkins Dr