Arts & Entertainment

The New West: Saying a sad farewell to “the cowboy conductor” and civil rights elder

Published

5 years agoon

Posted By

Outlaw Partners

By Todd Wilkinson EBS Environmental Columnist

Three years ago, after Robert Staffanson penned his award-winning memoir at the ripe young age of 94, veteran journalist Ed Kemmick from Billings posed this question after giving the book a rave review: “Is Staffanson the most interesting man in Montana?” he asked.

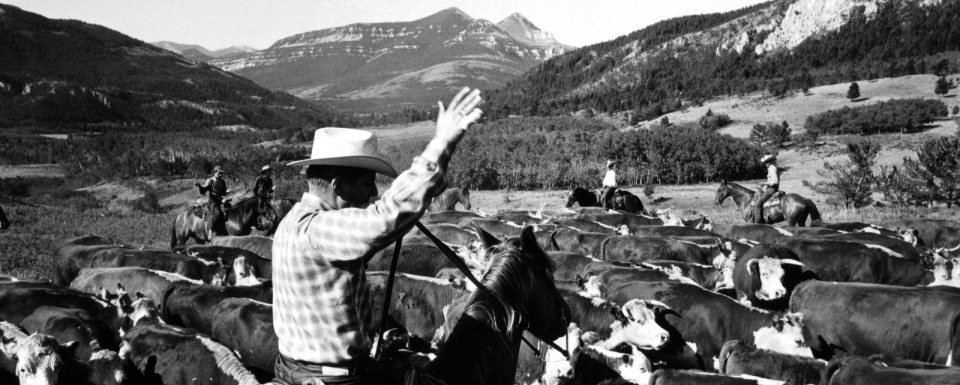

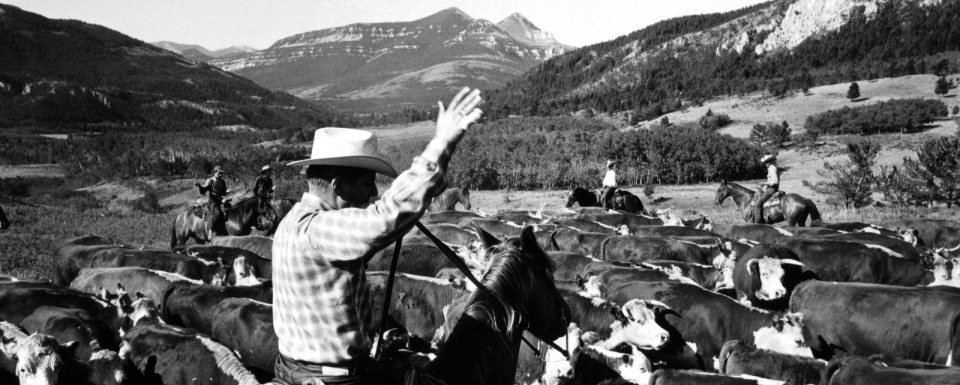

Staffanson’s three-part tome, “Witness to Spirit: My Life with Cowboys Mozart and Indians,” which I helped edit, chronicled his life as a rancher’s son who underwent several different phases of reinvention.

Born in Sidney astride the badlands and prairie country of the Lower Yellowstone River, raised on a cattle ranch in the mountainous Deer Lodge Valley on the other half of the state, then trained in music at the University of Montana, Staffanson, who would become known as “the cowboy conductor” was on an unlikely trajectory.

Upon college graduation, Staffanson helped establish The Billings Symphony, was subsequently tapped, based upon the recommendation of one of the most famous conductors in the world, to lead the Springfield Symphony in Massachusetts, and then, in the prime of his career, he gave it all up as he entered midlife to embrace the role of activist.

Returning home to his beloved West, he played a catalytic role in establishing the American Indian Institute while becoming a tenacious and formidable advocate for native rights, cultural preservation and imploring society to recognize the ancient wisdom of indigenous people.

Staffanson died Saturday, April 27, 2019, at age 97 in Bozeman and a memorial celebrating his life happened last weekend, with indigenous elders from across the country coming to the service.

Staffanson came into the world on Nov. 11, 1921, the son of parents George and Julia Staffanson. He credited his father with being “an agrarian man of the earth” who was good with animals and filled the space of their modest farm house playing live fiddle music—the nucleus for Bob learning to master several different instruments.

As for his mother, she taught him that cowboys need not be stoic or model their behavior after fictitious Hollywood stereotypes, that the image of rugged individualists was a myth, and that what really held rural Western society together, transcending divisions, was a broader sense of community and citizenship based on mutual respect, good manners, honesty, integrity and understanding that spirituality comes in many forms.

As Staffanson wrote in the first line of his memoir, he loved horses. The first steed he ever rode, at age 4, was a pony ironically named “Injun” that his father had purchased from traders with the Salish-Kootenai. Even as a nonagenarian, he would weep recounting his friendship with the horse, recalling the day it had to be euthanized as it succumbed to infirmity in old age. He longed to have known what the horse’s original name had been, imparted by its first native caretakers.

Staffanson spent his coming-of-age years on the family cattle ranch outside Deer Lodge. He remembered, in the 1930s, following well-worn trails established by tribes who came to Montana’s high plains on bison hunts. A skilled horseman, he, in reflection during the autumn of his life, wrote lyrically about ranching, the close bonds that riders have with their horses, and the nuances of tack.

On weekends during his younger years, he shed his blue jeans and cowboy hat and performed with bandmates who traveled from town to town as favorites on the dance hall circuit.

In 1945, Staffanson married his hometown sweetheart from Deer Lodge, Frankie Ann Smith, and, because of that alone, he always considered himself “the luckiest man on earth.” They were married for 71 years.

After graduating from the University of Montana, a headstrong Staffanson went to Billings and established its first symphony, stubbornly defying critics who claimed that enough talent could never be harnessed there to do justice to the works of great composers. A friend once said of Staffanson: “Don’t ever tell Bob that something can’t be done because he’ll take it on and recruit you to help make it happen. If you’re hesitant, his enthusiasm and fearlessness will win you over.”

It was during a trip back east, amid a clinic hosted by the eminent Eugene Ormandy, the Hungarian-American violinist and conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, that his life took another dramatic turn. In a telltale moment captured in his book, Ormandy took a liking to the thirtysomething Staffanson, whom he fondly dubbed “the cowboy conductor from Montana.”

Impressed by the kid’s spirit, Ormandy opened doors for Staffanson, helping him land a prestigious post as conductor of the Springfield Symphony in the Berskshires of western Massachusetts. During his decade and a half tenure there, he became friends with many of the giants, including Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Fiedler, all of whom adored Staffanson’s wife, Ann.

Every summer during symphony recess and when they weren’t traveling in Europe, the Staffansons returned to Montana and enjoyed taking road trips to places where history happened. Staffanson had high praise for the Grand Teton Music Festival and knew many of its musicians.

During one homecoming, “Look” magazine featured a long story about “the cowboy conductor.” Half his life ago, Staffanson had grown increasingly appalled by the marginalization of indigenous people and he became a lifelong student of tribal lifeways.

“Any conscientious human who becomes awakened to injustice cannot pretend it does not exist once he or she becomes aware,” he said. “As decent people, we can’t close our eyes. My conscience, as a Christian, wouldn’t let me do that, but this is a value embraced by any religion.”

In the late 1960s, after forging close friendships with a number of elders from various tribes, Staffanson was invited to attend a camp with the Bloods in southern Canada. Something unexpected happened on that visit: Bob said he had a supernatural experience and it radically transformed how he thought about the human relationship with nature.

Shaken, he decided to leave conducting permanently behind, seeking new ways of addressing what he called, “America’s greatest moral failure: it’s treatment of its first human inhabitants.” As he noted, such a radical departure needed Ann’s approval. “We were a team,” he said.

There were long discussions. A measure of Ann’s character and love, he said, was her agreement to leave a prestigious position for an unknown future in the troubled world of race relations.

“Few, if any, women would have acquiesced to a change that dramatic. If she had objected, it would not have happened,” he said.

Given his affinity for history, Staffanson worked briefly as assistant director at the then Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Around this time, he fell ill and almost died while hospitalized in Billings. The medication he was prescribed ended up damaging his audio faculties, resulting in a hearing loss that over the years deepened and ultimately reached 95 percent, forcing him to communicate by reading lips.

While struggling with this near-debilitating setback that stole away his most perceptive sense—listening—that had allowed him to thrive as a conductor, Bob and Ann welcomed their daughter, Kristin Staffanson Campbell, whom they considered “the brightest light in their lives.”

Resettling first in Helena and then in Bozeman, Staffanson acted on his frustration of not being able to help his native friends by laying the groundwork for the American Indian Institute, which is still operating today under the dynamic direction of young native leaders. Along the way, Staffanson learned a humbling lesson: the indigenous community, he said, had deep and justifiable distrust when it came to white people carrying forth a savior complex promising to aid Indians in their plight.

Initially, he encountered fierce criticism from activists in the American Indian Movement who questioned his motivation. Not only did Staffanson receive reticence from native leaders who eventually came to trust him, but his advocacy for indigenous rights brought derision from some white people he knew. On one occasion, a person he knew well accused him “of betraying his own race.”

The American Indian Institute, with elders leading the way, hosted a gathering of dozens of tribes at the Missouri headwaters near Three Forks, the first of its kind. Later, the institute worked with Ted Turner to stage the first major encampment of native tribes at Turner’s Flying D Ranch near Bozeman in over 130 years. Sharing stories, rituals and memories, the event focused on tribal relationships with bison.

Staffanson savored friendships he cultivated in the classical world, with musicians, other conductors, their families and innumerable fans who turned out to hear performances of his orchestras. But he held a special place in his heart for the thousands of native people he met, not only from North America but around the globe. Be it elders or young people, he stood in awe and ever-deepening humility of the time-tested knowledge accrued by those who lived in tune with nature.

“You can travel the world over and among indigenous peoples there is a deep mutual knowing that transcends any language barriers. People whose persistence and lifeways flow out of their relationship with the Earth have a kindship of profound mutual understanding,” he said. “There’s this perception that people love the image of the cowboy. Yes, it’s true, but I can tell you the world loves Indians more. Everywhere we went, I saw how well-regarded indigenous people from this continent were. They were viewed, embraced, as the first real authentic Americans.”

The Lakota have a phrase, “Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ,” which means “all are related.” Staffanson said every tribe has its own version. “They see the harmony. They see the way the world fits together and is united in ways that are unfortunately invisible to many of us,” he said recently. “They see the sentience and interdependence between humans and all living things. There is so much we can learn. My own understanding is only beginning.”

Just when you thought you had Staffanson pegged, he would amaze you again. While working on his book—he dreamed of being a writer—he divulged that he quietly had carried on back and forth correspondence with two of America’s greatest nature writers, Wendell Berry and Barry Lopez. He gained admiration from them and others. Berry told Staffanson he needn’t worry. He was a writer, a damned fine one. In 2017, Staffanson penned a piece, at age 96, titled “What It Means To Be A Real Cowboy” for “Mountain Journal” that was widely circulated nationally and read more than 100,000 times.

Terry Tempest Williams, who until recently had a home in Jackson Hole, wrote after reading a draft of Staffanson’s book, “Robert Staffanson has created a story that honors his own evolution from cowboy to symphony conductor before abandoning wealth and fame to work with indigenous people and learn the ways of wisdom. This is a book that reminds us our lives are blessedly made of stories. Gratitude is the word that remains after reading ‘Witness to Spirit’.”

Staffanson’s favorite composition, Barber’s “Adagio for Strings,” was played in its entirety at the memorial last weekend. For several elders in the audience, tears flowed.

Todd Wilkinson is the founder of Bozeman-based Mountain Journal (mountainjournal.org) and is a correspondent for National Geographic. He’s also the author of “Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek” about famous Jackson Hole grizzly bear 399, which is available at mangelsen.com/grizzly.

The Outlaw Partners is a creative marketing, media and events company based in Big Sky, Montana.

Upcoming Events

april, 2024

Event Type :

All

All

Arts

Education

Music

Other

Sports

Event Details

Children turning 5 on or before 9/10/2024:

more

Event Details

Children turning 5 on or before

9/10/2024: Kindergarten

enrollment for the 2024-2025 school year can be completed by following the

registration process now.

Children

born on or after September 11, 2019: 4K enrollment is now open for

families that have a 4-year-old they would like to enroll in our program for

the 2023-2024 school year. Please complete the 4K Interest Form to

express your interest. Completing this form does not guarantee enrollment into

the 4K program. Enrollment is capped at twenty 4-year-olds currently

residing within Big Sky School District boundary full time and will be

determined by birth date in calendar order of those born on or after September

11, 2018. Interest form closes on May 30th.

Enrollment now is critical for fall preparations. Thank you!

Time

February 26 (Monday) - April 21 (Sunday)

Event Details

Saturday, March 23rd 6:00-8:00pm We will combine the heart-opening powers of cacao with the transcendental powers of breathwork and sound. Together, these practices will give us the opportunity for a deep

more

Event Details

Saturday, March 23rd 6:00-8:00pm

Time

March 23 (Saturday) 6:00 pm - April 23 (Tuesday) 8:00 pm

Location

Santosha Wellness Center

169 Snowy Mountain Circle

Event Details

We all are familiar with using a limited palette, but do you use one? Do you know how to use a

more

Event Details

We all are familiar with using a limited palette, but do you use one? Do you know how to use a limited palette to create different color combinations? Are you tired of carrying around 15-20 different tubes when you paint plein air? Have you ever wanted to create a certain “mood” in a painting but failed? Do you create a lot of mud? Do you struggle to achieve color harmony? All these problems are addressed in John’s workbook in clear and concise language!

Based on the bestselling “Limited Palatte, Unlimited Color” workbook written by John Pototschnik, the workshop is run by Maggie Shane and Annie McCoy, accomplished landscape (acrylic) and plein air (oil) artists,exhibitors at the Big Sky Artists’ Studio & Gallery and members of the Big Sky Artists Collective.

Each student will receive a copy of “Limited Palette, Unlimited Color” to keep and take home to continue your limited palette journey. We will show you how to use the color wheel and mix your own clean mixtures to successfully create a mood for your paintings.

Each day, we will create a different limited palette color chart and paint a version of a simple landscape using John’s directives. You will then be able to go home and paint more schemes using the book for guidance.

Workshop is open to painters (oil or acrylic) of any level although students must have some basic knowledge of the medium he or she uses. Students will be provided the book ($92 value), color wheel, value scale and canvas papers to complete the daily exercises.

Sundays, April 14, 21 and 28, 2024

Noon until 6PM.

$170.

Time

14 (Sunday) 12:00 pm - 28 (Sunday) 6:00 pm

Event Details

Come join us at Cowboy Coffee as we celebrate a fun night of drinks, games, and meeting others within the community. This event is from 6-8 and all are welcome

Event Details

Come join us at Cowboy Coffee as we celebrate a fun night of drinks, games, and meeting others within the community. This event is from 6-8 and all are welcome to come, if you don’t know who to bring come alone this is a great mixer event! This is an event hosted by Big Sky OUT as we work to provide queer safe spaces throughout the community.

Time

(Sunday) 6:00 pm - 8:00 pm

Location

Cowboy Coffee

25 Town Center Ave. Big Sky, MT 59716