By Jess Olson EBS COLUMNIST

Drought is a tricky phenomenon. Unlike the sudden, dramatic fury of a flood, or the fleeting inconvenience—or, blessing—of a snowstorm, it is a creeping, quiet paradox. Drought lacks a clear starting point and an obvious end, its presence revealed not by a single event, but by an accumulation of data points over time.

This subtlety of drought is part of what makes it so difficult to manage, and so dangerous to our sensitive water supply. Drought compromises our drinking water, affects our ability to protect against wildfire, impacts agriculture production, landscape irrigation, recreation, and wildlife habitat. It can trick us into a false sense of security, making it difficult to understand why, even during a rainy period with seemingly normal streamflows, our community and our resources are still subject to the impacts of drought.

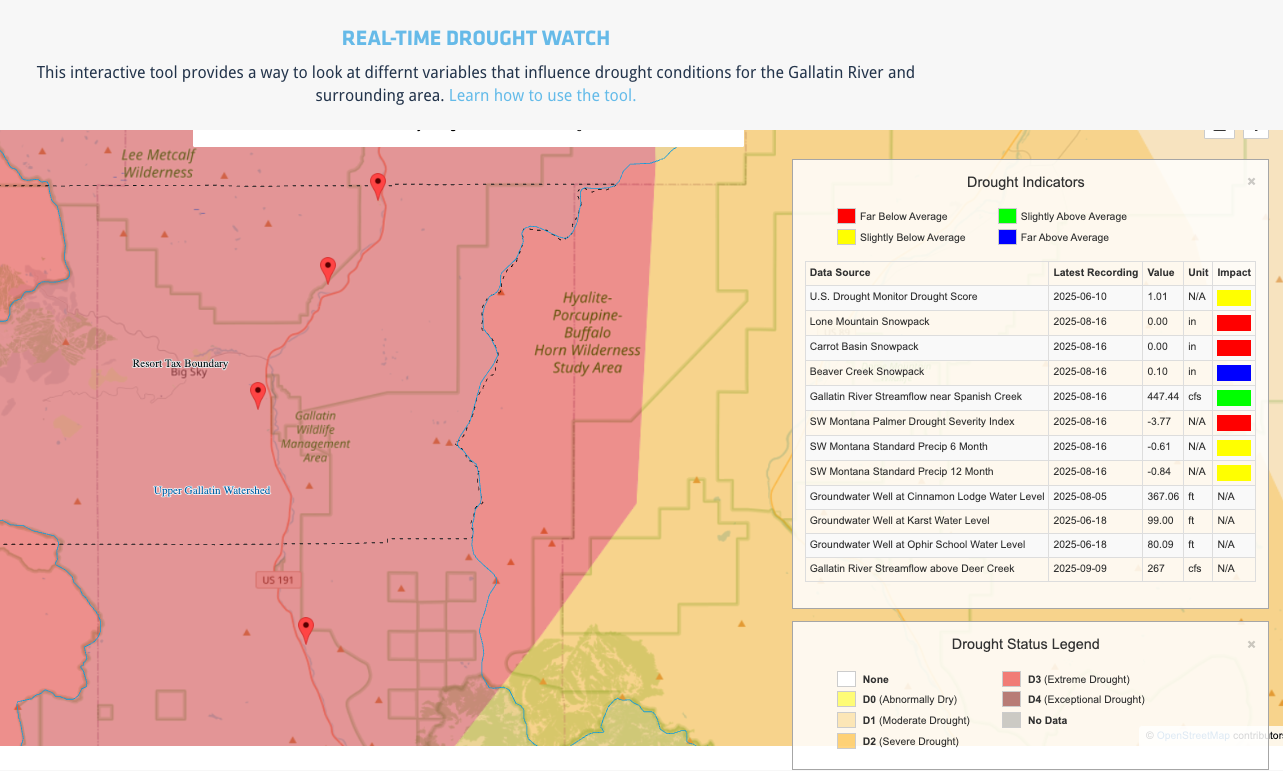

This is precisely the situation we face in Big Sky, where we are currently in D3 or Extreme Drought status. At the time you read this column, some indicators, like streamflows in parts of the Gallatin River and snowpack at Beaver Creek, are above average for this time of year. So how is it possible that we are still in drought? The answer lies in the multifaceted nature of this threat.

Defining drought is a complex task, with five commonly used definitions highlighting its different dimensions. Meteorological drought focuses on dryness and the length of a dry period, which can be region-specific.

Hydrological drought—what most people think of—is defined by precipitation, including rain and snowfall, and its impact on the hydraulic system, such as low streamflows and groundwater levels.

Agricultural drought links these factors to impacts on farming, focusing on soil water deficits and evapotranspiration. This type of drought is least related to the types of drought we refer to in Big Sky.

Socioeconomic drought considers the supply and demand of economic factors like the outdoor recreation industry, while Ecological drought, the most recently recognized definition, focuses on the stress prolonged water deficits place on local ecosystems and species such as trout and other wildlife. So by definition, there are many categories and impacts that we consider when talking about drought in our region.

All these definitions have one thing in common: they rely on long-term data and regional specifics. A brief period of rain or a few above-average data points do not erase the long-term trends that have led us to this point. This is where the local expertise of the Gallatin River Task Force’s Drought Status comes in. While the U.S. Drought Monitor, an excellent tool developed by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, provides a broad snapshot of drought across our country, it’s not designed to capture the specific nuances of individual communities. By combining the U.S. Drought Monitor with our own local metrics—snowpack levels at Lone Peak, Gallatin River streamflow, groundwater levels, and more—our dashboard provides a drought status that is truly specific to Big Sky.

The dashboard uses twelve metrics to determine our status, and sometimes, these metrics can contradict one another. This is why we can experience a stage three drought during a rainy period. The rain may temporarily boost streamflows, but it may not be enough to replenish depleted groundwater reserves or restore soil moisture levels after a prolonged dry spell. A single rain event doesn’t magically fix a problem that has been building for months or even years. Individual factors, even in combinations, do not give us the full picture of drought.

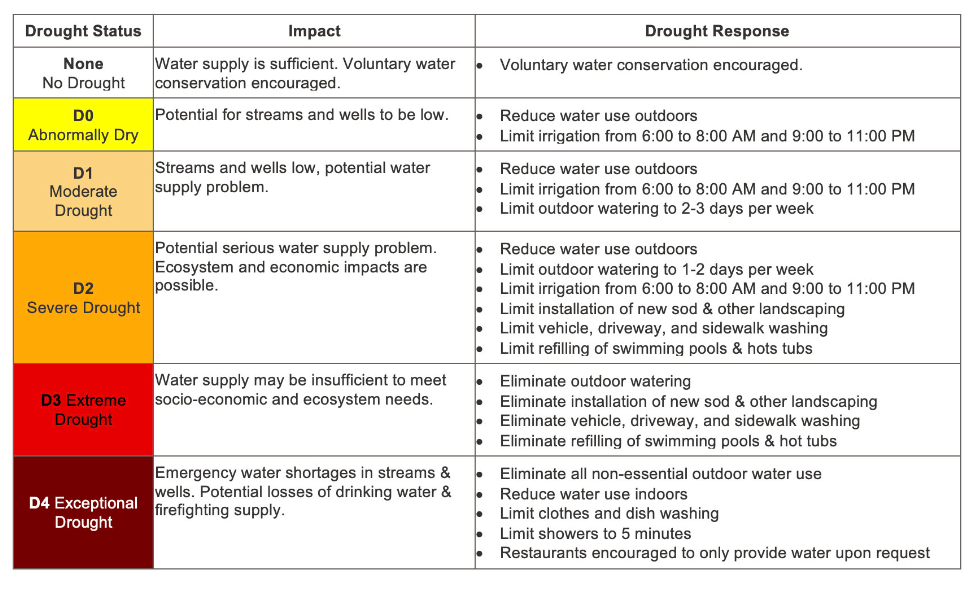

The scale for defining drought stages—from D0, Abnormally Dry, to D4, Exceptional Drought—is our go-to for understanding the severity of the situation. Currently, Big Sky is in a serious, D3, Extreme Drought, where widespread water shortages are a reality. And while we cannot control the amount of snow that falls this winter or how quickly it melts, we are not powerless.

Community-level water conservation is one of the most effective and environmentally friendly ways to protect our water supply. The actions we take now, as a community, can make a real difference. By understanding the complexity of drought and the importance of our local data, we can move beyond the confusion and take meaningful steps to safeguard our most precious resource. Education and understanding drought is key; taking our own measures to do what we can in our own homes and businesses and as a community is essential to protecting our already fragile water supply during these exceptional times of drought. To stay up to date on our drought status and learn what measures you can take, visit the tool online.

Jess Olson is the Conservation Manager at the Gallatin River Task Force. She manages the Task Force’s Water Conservation Program and holds a Qualified Water Efficient Landscaper certification to help you with your water-wise projects.