By Abby Butler EBS COLUMNIST

Fishing, hiking, biking, skiing, hunting—it’s what life in Montana is all about. Blue ribbon trout rivers, world-class skiing, and trails with breathtaking views and abundant flora and fauna make up this incredible landscape we call home. But what if our favorite activities had the potential to cause harm and even take away access to our favorite places?

If you’ve been following along in this series thus far, you can probably guess the culprit—invasive species. These plants, animals, and even microscopic pathogens, once introduced, wreak havoc on our environment. With adaptations that facilitate their rapid spread through a landscape, invasive species quickly take hold and take over. But what vector is the fastest of them all? Unfortunately, it’s us.

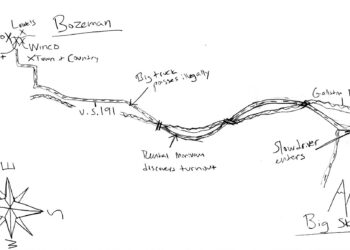

Let’s start with Montana’s blue ribbon trout fisheries. The Gallatin River might be too fast for an invasive dreissenid mussel to survive, but that won’t stop curlyleaf pondweed and Myxobolus cerebralis from leaving their impacts. Curlyleaf pondweed, an invasive, aquatic plant, is already in Hebgen Lake where it’s working hard to form dense mats that block sunlight to native plants and limit access to recreation for boaters and paddlers.

According to MT Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Myxobolus cerebralis, a microscopic parasite responsible for whirling disease in salmonids, has the potential to devastate Montana’s wild and native trout fisheries. Targeting juvenile fish, Myxobolus cerebralis causes deformities to the spine and tail, which can lead to uncontrollable whirling behavior where affected fish swim in erratic circles. These fish are easy prey and have difficulty getting enough nutrients to survive.

Mountain bikers—you’ve heard that “clean bikes are fast bikes,” but they’re also responsible bikes. Whether you’re riding a mellow green, grinding out uphill miles, or hitting a dirt jump, your bike can be collecting all kinds of plant debris, most importantly, seeds. A dirty bike is inevitable at the end of a ride, but it shouldn’t be a common occurrence at the start. Oxeye daisy, a state-listed noxious weed, can produce 26,000 seeds per plant, with those seeds lying dormant in the soil for up to 39 years. That means the mud on your tires that picked up a couple of oxeye daisy seeds can impact your favorite trails almost 4 decades later. For trail builders and maintenance teams, invasive species mean less time improving erosion and trail safety, and instead more time trying to hold back the spread of weeds.

But what about skiing? Aren’t invasive plants dead or biding their time underground till the temperatures rise and the snow melts? That’s what weeds want you to think. Many weeds like spotted knapweed and the infamous houndstongue produce plant skeletons just waiting for you to brush by them so they can cover your gear with sticky seeds. This Big Sky ski patroller is proof that invasive species don’t take the winter off.

So, what’s the fix? It’s really as simple as cleaning your gear after each use. Following the practices of Clean.Drain.Dry and PlayCleanGo will ensure that your favorite activities aren’t spreading invasive species.

When you’re finished fishing on the Gallatin? Rinse your gear off (river water works great), drain any excess water, and let it dry before you head to your next spot. This is especially important if you frequently switch fishing locations.

When you’re done flowing through Mountain to Meadow, give your bike a quick rinse and brush off any dirt. This applies to hiking boots, ATV tires, and anything that collects dirt. Building habits like Clean.Drain.Dry and PlayCleanGo into your routine helps protect this beloved landscape and ensures access for yourself and future generations to come.

Have questions about invasive species? Visit Grow Wild’s website or contact the Madison or Gallatin County Weed District for more information. Join us in protecting the landscapes we all love.

Abby Butler is the conservation program coordinator for Grow Wild, a 501c3 nonprofit organization that works to conserve native species in the Upper Gallatin Watershed through education, habitat restoration, and collaborative land stewardship.