By Jessianne Castle ENVIRONMENTAL AND OUTDOORS EDITOR

GARDINER – Instruments in tow, Mike Poland set out for Steamboat Geyser in Yellowstone’s Norris Geyser Basin in mid-May, charged with replacing a data logger that quit working last fall.

Poland, the scientist in charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, was visiting Yellowstone from his home in Vancouver, Washington, for the spring and summer field season and was eager to reinstall instruments into Steamboat Geyser after the world’s tallest active geyser had a record-setting year in 2018.

“Steamboat’s really put on a fantastic show,” Poland said during a public presentation hosted by the National Park Service in Gardiner on May 17.

A year in review

Despite the failure of an on-site temperature gauge, scientists know Steamboat set a record last year with 32 eruptions—up from the 29 eruptions that went off in 1964—thanks to a water gauge in Tantalus Creek, where the geyser’s water flows.

About an hour after an eruption, Poland said the observatory’s water gauge records a spike in the amount of water coming through the creek. Between January and EBS press time on May 22, the geyser has erupted 17 times after experiencing multiple periods of dormancy and rejuvenation in recent decades.

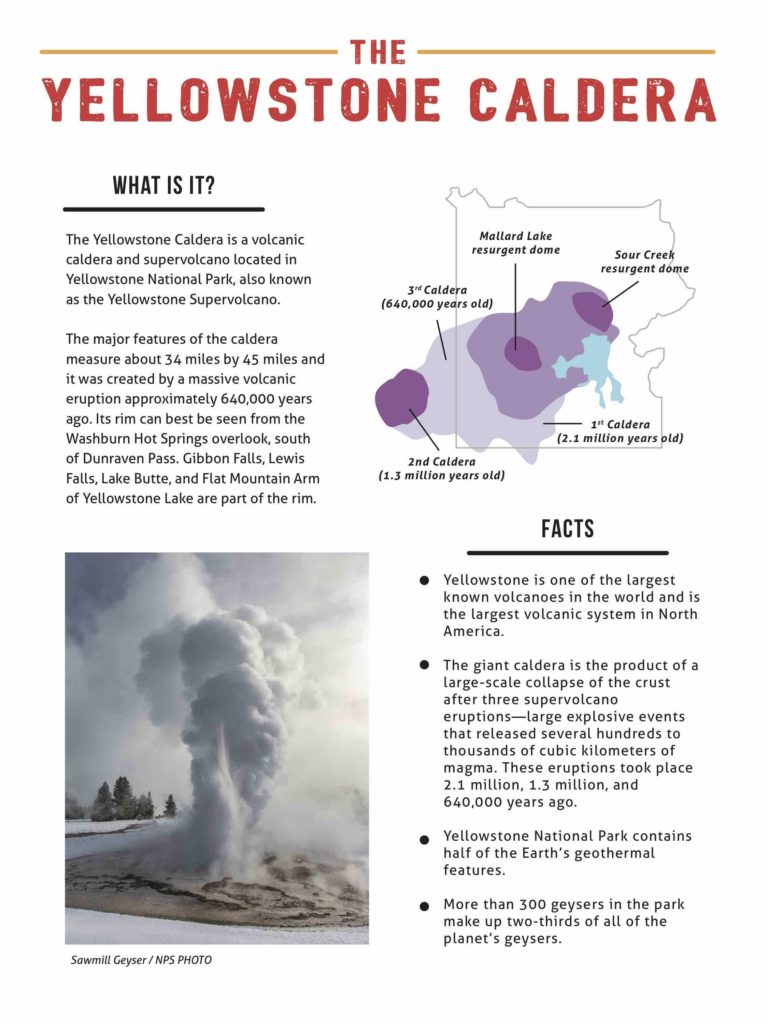

Temperature gauges and river sensors are just a few of the tools the observatory uses on a regular basis to monitor Yellowstone National Park and the active volcanic caldera below. The Yellowstone Volcano Observatory is a consortium of researchers from universities, the U.S. Geological Survey, Yellowstone National Park and the geoscience consortium UNAVCO, among others, and is responsible for the timely monitoring of Yellowstone’s volcanic, seismic and hydrothermal activities.

In addition to being a record-setting year for Steamboat Geyser, 2018 was host to additional new geyser activity, as seen when Ear Spring erupted in September for the first time since 1957, spewing decades worth of trash, as well as rocks and scalding-hot water.

Furthermore, research scientist Greg Vaughan identified a new thermal area near Tern Lake north of Yellowstone Lake after using a combination of satellite-based thermal infrared sensors and aerial photography. By comparing images taken over the last two decades, Vaughan has spotted the birth of a hydrothermal area that is currently on dry ground but is emitting heat and killing trees.

“This is Yellowstone being Yellowstone,” Poland said during the May lecture after providing a recap of the 2018 hydrothermal activity. “These hydrothermal systems are extremely dynamic … The only thing that you can count on is the fact that they’re going to change.”

Ground changes

Beyond changes in the hot water system at Yellowstone, the very ground has shifted as well.

For 24 years beginning in 1983, geologist Dan Dzurisin measured the way the ground moved in the nation’s first national park by exercising a practice known as leveling, whereby he carted surveyor’s instruments across miles of park roadway, taking height measurements on his surveyor sticks.

In 2007, this physical work was replaced by GPS technology and today numerous GPS units are scattered throughout the park as a way to record ground movement. But Dzurisin still interprets the GPS data.

Overall, the Yellowstone caldera experienced regular uplift for a number of decades, though beginning in 2015, the caldera began subsiding or slowly lowering back down. The Norris Geyser Basin on the northwest edge of the Yellowstone caldera has been behaving differently, though.

Dzurisin says the area has reacted in the almost exact opposite way as the rest of the region, indicating that something unique is happening in this thermal area. Based on the timing of an earthquake swarm that corresponds with a change from uplift to subsidence, scientists believe something must have sprung a leak.

It appears that something changed in the basaltic magma chamber during the late 1990s. Gas and water emitted from the magma slowly made its way toward the earth’s surface until it was trapped beneath an impermeable layer, where it accumulated and pressurized causing rapid ground uplift.

This carried on until a magnitude-4.8 earthquake hit Norris in 2014, which Dzurisin says must have fractured the rock that had trapped the gas and water. The ground began to recede once again, and carried on that way until two years ago.

“Now it’s going back up,” Dzurisin said. “We know from studies elsewhere that hydrothermal features are very good at repairing themselves. If you make a crack in an active hydrothermal area, it’s hot enough that the rocks can … ooze back and fill that crack. You can [also] have minerals form in the crack.”

The consensus, according to Dzurisin, is that the water and gas are likely trapped once again.

Proof of the volcano

With 30 years of research on Yellowstone’s ground, Dzurisin says for the first time he feels researchers have definitive proof of the magma-chamber theory beneath Yellowstone. Taking up the latter half of the May 17 presentation, Dzurisin described some of this proof.

For years, scientists have believed the thermal features in Yellowstone are an expression of a heat source deep beneath the ground that extends down to the core of the earth. This is known as a hot spot, and creates an area of melting rock and magma that is likely to have been present for at least 20 million years.

While the hotspot is fixed within the earth, the plates at the surface are able to move. Combined with periodic volcanic eruptions, this phenomenon has created the long line that forms the Snake River Plain, which ends at Yellowstone National Park.

Based on the speed and movement of seismic waves that occur when Yellowstone experiences as many as 2,500 earthquakes each year, scientists have developed an idea for what is happening below ground.

They suspect that the hotspot extends from the core of the earth to about 40-50 miles below the earth’s surface. Above this rests a pot of basaltic rock and magma that is likely 20 miles belowground. A second magma chamber rests on top of this and is composed of rhyolite, a very sticky magma that collects gases and is highly explosive upon reaching the service. This chamber is between 3 and 10 miles down.

While the thought of molten magma only a few miles below your feet is certainly startling, Poland and Dzurisin say it isn’t cause for alarm.

“These are not massive chambers of magma,” Poland said, adding that only about 2-15 percent of the actual rock chamber is liquid magma. “It’s really mostly solid rock. Hot rock, but mostly solid.”

Poland added that the last time the volcano erupted was about 631,000 years ago, and the last time magma reached the surface was 70,000 years ago.

Dzurisin said scientists also consider the amount of heat and CO2 that comes out of Yellowstone as proof for a basaltic melting pot deep below ground. The temperature from all of the park’s thermal features produces an estimated 1.3 gigawatts of power—which is more than enough power to send Doc’s DeLorean back in time from the 1985 movie “Back to the Future.” Approximately 35,000 tons of carbon dioxide comes out of the ground in Yellowstone every day.

“That’s a tremendous amount of CO2,” Dzurisin said, but he was quick to add, “That’s a very small amount compared to other natural sources so it’s not a major contributor to climate change.

“The only way you can make those numbers is by having a tremendous flux of basalt coming up out of this mantle plume,” he explained.

Dzurisin is excited that so much is going on in Yellowstone National Park, but said the activity is “as normal as grizzly bears.”

“It’s what Yellowstone does,” he said. “What’s new is that we’ve been able to confirm all of that … Like the grizzlies, Yellowstone should be enjoyed not feared.”

For more information, visit volcanoes.usgs.gov/observatories/yvo.