His impact as “The Father of American Conservation” written across today’s West

By Todd Wilkinson EBS ENVIRONMENTAL COLUMNIST

George Bird Grinnell is a towering and, in many ways, uneclipsed figure you ought to know about, not just because he has a melting glacier and other landmarks named after him in Glacier National Park. Or because— or perhaps in spite of— the fact he is likely to be dismissed by some in the “critical theory” community as one of those New York elitist, 19th-century, white-guy conservationists who matriculated at a place like Yale.

Grinnell’s influence actually factors into so many things today shaping our modern perception of the public land American West that his impact can only be described as colossal, even by detractors. It’s why many say Grinnell—not John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt or Henry David Thoreau— deservedly earned the title “the father of American conservation.”

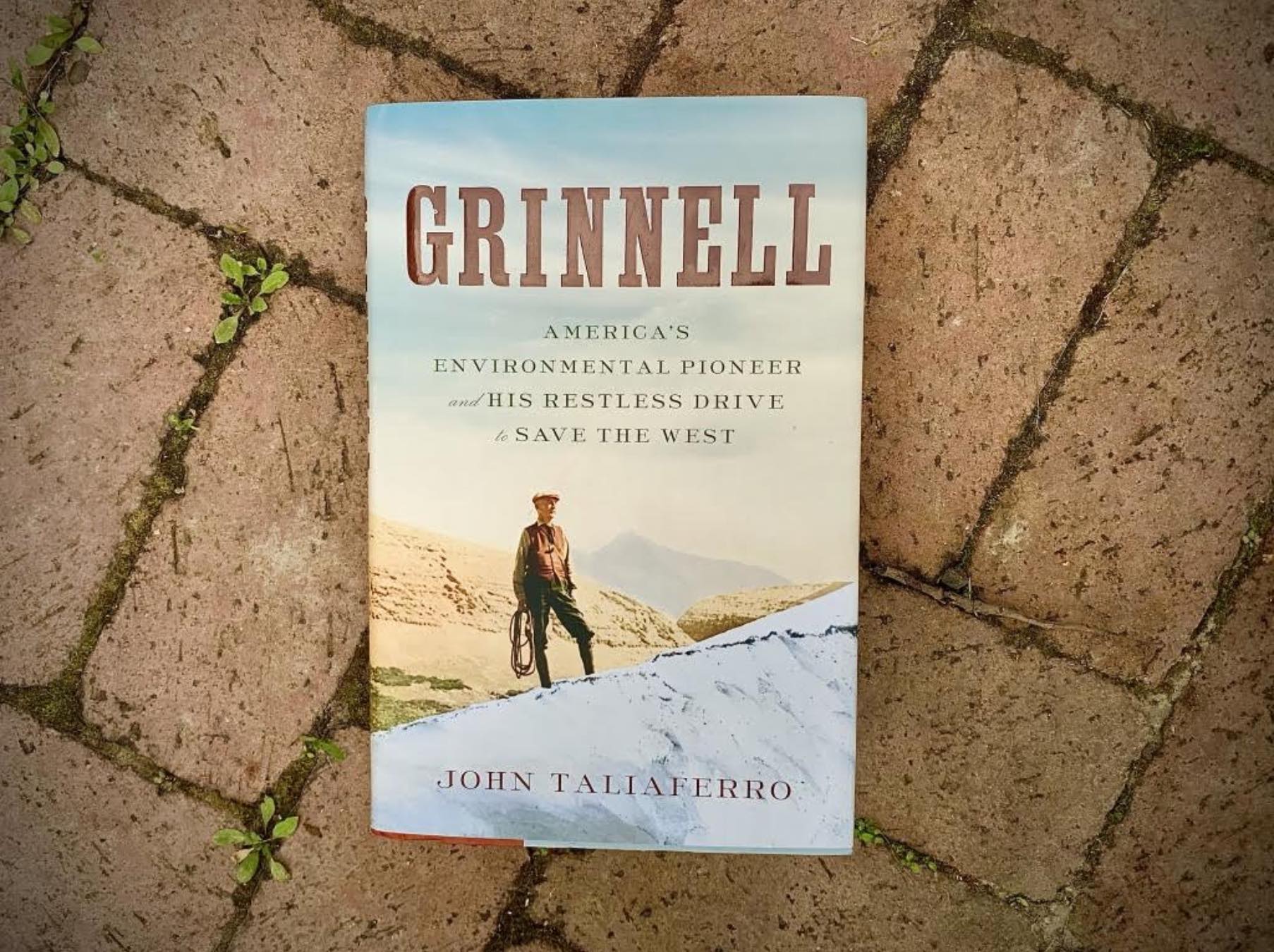

In John Taliaferro’s new fascinating biography, “Grinnell: America’s Environmental Pioneer and His Drive to Save the West,” his subject rises as a pathfinding historic connector between people with big enduring ideas and landscapes—many of which continue to evolve.

Thanks to Grinnell’s tenacious love of Yellowstone, he foresaw, as a naturalist, the need to enlarge the park or at least secure winter range outside it for migrating wildlife, which would’ve resolved many current-day controversies. He also helped prevent portions of our first national park from being sacrificed to the whims of water developers who wanted to dam two park rivers and make the storage available for irrigating crops and livestock.

If you have a soft spot in your heart for indigenous people, then it’s essential to point out that Grinnell, as an ethnographer and author, evolved into becoming a fierce ally and friend of several different tribes in our corner of the West.

If you venerate Theodore Roosevelt, then you’ll want to know how important Grinnell was in building TR’s legacy, getting behind the cause of saving bison and elk from extinction, and protecting public lands in their nascent beginnings from robber barons.

If you hunt and fish, then crucial is understanding that Grinnell helped wordsmith many of the tenets Roosevelt advanced for fair chase and ethical hunting when they founded the Boone & Crockett Club, laying the groundwork for what we today call the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

If you admire—or despise—the preservationist Muir, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, George A. Custer, Aldo Leopold, Gifford Pinchot and Phillip Sheridan, then you’ll find it intriguing to know Grinnell was an acquaintance of them all and more.

Over the years, Taliaferro who lives part of the year in Paradise Valley, Montana, has distinguished himself as a gifted, incisive author.

Except in rare circumstances, Grinnell (1849-1938) often received lighter-brush reference in discussions of pivotal historic conservation events. Yet he figured in the center of most of them. As editor and contributor to Forest & Stream magazine for decades, Grinnell played a catalytic role in calling his readers’ attention to events happening in the distant West on the other side of the Mississippi.

Grinnell commented with edifying authority on the West, having made his first trip in 1870, two years prior to Yellowstone’s creation, and four years before he joined Custer’s controversial exploration of the Black Hills; fortunate for him, Grinnell wasn’t riding along with Custer at the Little Bighorn in 1876.

Taliaferro discovered a mother lode of material, thanks to communication with Grinnell descendants. He gained access to 40,000 pages of correspondence Grinnell had with important people, plus 50 personal diaries and notebooks, and an unfinished autobiography.

Taliaferro delivers the goods and what a rich cache it is. The easy flow of his narrative is much like reading Stephen Ambrose’s award-winning biography, Undaunted Courage, about the Lewis & Clark expedition.

Grinnell grew up in New York City on the estate where painter and ornithologist John James Audubon had lived. Later, he helped established the National Audubon Society and the New York Zoological Society. He also went on a bison hunt in Kansas and joined the famous fossil-hunting expeditions carried out by paleontologist O.C. Marsh.

In his later years, Grinnell realized that the fight to keep even the most venerated places protected is never ending. The very same raiders who opposed Yellowstone’s creation in 1872 were continuously looking for ways to exploit the park.

Then, of course, there are Grinnell’s dealings with native people.

One reviewer of Grinnell wrote in The Wall Street Journal: “The man was not ahead of his time but embedded within it, acting with the lofty confidence typical of the patrician WASP milieu in which he lived and operated, never more apparent than in his condescension toward the very same Native Americans he sought to defend. And yet he stands (far) apart from fellow conservationists such as Theodore Roosevelt and Madison Grant, whose ideas on race can only be described as repugnant.”

“Grinnell” is an essential book for anyone who cares about the West and American conservation but also what it means to battle for cause even though you know its purpose might not be fully realized until long after you’re gone.