A bear biologist, a rancher and an outfitting representative weigh in on Montana’s grizzly management plan.

By Amanda Eggert MONTANA FREE PRESS

Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks is expected to adopt a plan this spring that will, in the event of a federal removal of grizzly bears from endangered species protections, guide state management of one of the West’s most iconic species. To better understand how that plan has been received, Montana Free Press spoke with three Montanans representative of prominent voices in the grizzly management conversation: a retired federal bear biologist who’s now a leading voice in conservation circles, a Rocky Mountain Front rancher living among an expanding and dispersing population of grizzlies, and an outfitting industry representative who calls for local authorities to have a greater control over natural resource management. They shared their perspectives on federal versus state management, establishing a grizzly hunting season, and the challenges of coexisting with an apex predator.

‘A TONE OF INTOLERANCE’

Missoula-based wildlife biologist Chris Servheen had been leading the federal grizzly bear recovery effort for 20 years when he was asked to help decide the fate of a mother grizzly that had been grievously wounded by an elk hunter she’d startled. After shooting the sow in the face with a high-caliber rifle, the hunter reported his run-in with the bear and her three cubs to state officials, who dispatched a Rocky Mountain Front-based state bear biologist to determine if the shot had been fatal.

It turned out not to be. The shot knocked the 16-year-old grizzly unconscious, but she eventually got up and continued going about her business.

Except that she didn’t — not quite. December of 2002 came and went, then January of 2003. Grizzly 144 and her cubs continued to wander up and down the Front, a dramatic, sparsely populated piece of country that residents refer to as a “wild working landscape.” The sow kept her 1-year-old cubs away from people, but kept circling the same piece of ground when she should have been heading into her den for the winter.

The state bear biologist, who’d been using radio collar data to track Grizzly 144 and her cubs, asked Servheen to weigh in on available options. Ultimately the biologist decided to intervene, hoping to prod 144 and her cubs into hibernation to preserve their remaining fat stores.

On a windy February day so cold that he worried the tranquilizer would freeze, the biologist immobilized the sow with a dart he shot from a helicopter. A wildlife veterinarian injected her with a heavy dose of antibiotics, removed bone fragments from her head and sutured her gunshot wound. Then the biologist installed Grizzly 144 in a large, hay-insulated culvert trap he’d moved onto the Blackleaf Wildlife Management Area, which had been closed to the public for the winter. The biologist waited for 144’s cubs to join her in the trap and then closed it on all four bears.

Then the biologist waited to see if 144 and her cubs would hibernate, if she’d regain her seasonal instincts, if her cubs would survive.

Servheen said the episode, long ago as it was, sticks with him still. Even now, six years into semi–retirement, Servheen said his thoughts sometimes turn to grizzlies he’s seen, heard about or personally handled in the course of his 35-year career leading the federal government’s effort to help the species recover.

Those thoughts come into sharper focus now that Servheen’s former employer, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is taking a closer look at delisting Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem and Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzlies. If the agency successfully removes those populations from the United States’ list of endangered and threatened species, Montana will take over management of its state animal, assuming a level of authority it hasn’t had since Lower 48 grizzlies became one of the first species placed on the endangered list in 1975.

Once a leading proponent of grizzly delisting who helped bring about a fivefold increase in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s grizzly population, Servheen now calls for Montana policy makers to pump the brakes and take a more conservative approach to managing intentional and unintentional grizzly bear deaths. More specifically, he’s concerned that Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks’ draft management plan, which it released to the public in December, reflects a politicization of predator management in Montana. It’s a “disappointing” plan, Servheen said, written with an overall “tone of intolerance.”

It focuses more on establishing a hunting season than on conflict prevention, he said, and fails to address bear mortalities arising from laws the Montana Legislature passed in 2021 seeking to reduce predator populations, which he calls the “dead elephant in the corner.” He’s also displeased that the draft plan allows hunters and wildlife managers to kill non-conflict bears traveling between recovery zones rather than supporting those bears’ movements in order to achieve a long-time recovery goal — interbreeding of isolated populations living between northwest and southwest Montana.

“We live in the place in the Lower 48 states that has the most grizzly bears and we should be real proud of that instead of trying to figure out ways to kill them and reduce their distribution as soon as they’re delisted,” Servheen, now chair of the Montana Wildlife Federation Board, said in a January conversation with Montana Free Press. “We don’t believe that’s the way we should manage the state animal.”

An experienced reader and writer of management plans, Servheen offered 18 pages of detailed comments on the 217-page plan on behalf of MWF, the state’s oldest and largest conservation organization. It’s irresponsible, he said, to allow hunting of groups of bears — mothers with their young, for example — particularly given the species’ slow reproductive rate. He’d also like the plan to include more direction as to how state wildlife managers will prevent hunters and trappers from inadvertently maiming and killing grizzlies given newly relaxed wolf hunting and trapping regulations that now authorize the use of neck snares and hunting with bait. The recent re-legalization of hunting black bears with hounds will also lead to conflict and grizzly bear deaths, he maintains.

Servheen’s comments also include a call for further monitoring. He’d like the state to track all grizzly mortalities, not just those that occur inside existing recovery zones. He questions the state’s ability to maintain a sustainable population if wildlife managers are monitoring the death or removal of bears only inside the Greater Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide ecosystems.

Asked if there’s one thing he wishes were more commonly known about grizzlies and their management, Servheen said the animals are not a “specter on the landscape” and are generally inclined to avoid people so long as humans make some accommodations to the realities of sharing a landscape with an apex predator.

‘JUST ANIMALS THAT LIVE ON THE PLANET THAT NEED TO BE MANAGED SO PEOPLE CAN LIVE HERE, TOO’

Valier cattle rancher Trina Bradley has had “all of the encounters with bears,” she says. When she was growing up near Dupuyer (population 93) her family found the animals digging in their vegetable garden, sitting on their front steps, climbing on their swing set. One of her brothers was chased by a grizzly when he was a teenager. Last year, another brother encountered them twice while working on his ranch.

“They’re everywhere,” she said. “My daughter didn’t get to play outside when she was little because it wasn’t safe. If I wasn’t out there with a gun in hand, she could not play outside.”

Like her father before her, Bradley has given voice to the predation-related concerns of agricultural producers living along the Rocky Mountain Front, a wild landscape formed by the 10,000-foot peaks of the Northern Rockies dropping into the high plains. As executive director of the Rocky Mountain Front Ranchlands Group and chair of a Montana Stockgrowers Association subcommittee on endangered species, much of Bradley’s work these days involves predator management.

There’s a difference, Bradley said, between wild bears and habituated bears — grizzlies that have become so accustomed to human presence they no longer fear and therefore avoid people.

“Because they were so mismanaged for so long, we have a lot of bears that shouldn’t be here,” she said. “Because they weren’t removed, now there are generations of high-conflict bears on the landscape.”

She said she would like the state to take over grizzly management and use a firmer hand to discourage the animals from living so close to people, particularly as their range stretches ever farther into the sparsely populated — and largely privately owned — plains of central Montana. It shouldn’t be acceptable for bears to be in and among her and her neighbors’ buildings and outbuildings, she said, noting that a grizzly can do considerable damage to an agricultural producer’s property by feeding on their crops — peas, barley, chickpeas — or digging up natural food sources like wild onions and gophers.

As Bradley sees it, the Rocky Mountain Front is saturated with grizzlies, and has been for some time. While she and her husband have strung an electric fence around their chicken coop, adjusted how and when they turn calves out in the spring, and modified their summer pasture rotation to avoid run-ins with bears, they remain an ever-present issue.

“For us, grizzlies are 24-7 neighbors,” she wrote in a September column published in the Choteau Acantha. “The stress of living with an apex predator affects us every day of the year.”

In 2019 and 2020, Bradley served on the Grizzly Bear Advisory Committee convened by then-Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, which she described as “an awesome and frustrating” experience. Overall, she said, she’s pleased that many of the committee’s recommendations are reflected in the draft plan FWP released for public comment in December, but there are a handful of things she’d like the department to change or clarify.

Bradley is emphatic that grizzly bears’ position in the food chain shouldn’t lead people to manage them any differently than other wildlife.

“People don’t see grizzly bears and wolves as wildlife — they see them as some magical unicorn, and they’re not that,” she said. “They’re just animals that live on the planet that need to be managed so people can live here, too.”

Successful management, Bradley said, won’t arise from single solution. It isn’t just a matter of putting up electric fences and removing carcasses, nor is bear conflict a problem that can be fixed with deterrents such as livestock guardian dogs or noise cannons alone. “All of them are important,” she said. “All of them need to be utilized.”

Bradley said policy makers should commit public funds to Front residents to deploy such tools, particularly given how much habitat agricultural lands provide for grizzlies and other wildlife. “The financial burden needs to be spread more fairly,” she wrote in the Acantha column. “Right now, Montana livestock producers, management agencies and conservationists are trying to raise public funds to get more of these tools on the ground, but there is always a need for more.”

Bradley supports a grizzly bear hunting season. It could give sportsmen and sportswomen who might otherwise be indifferent to — or even opposed to — grizzly bears’ presence in Montana a “dog in the fight,” she said. “That would bring in a whole ’nother demographic that would support conservation of grizzly bears.”

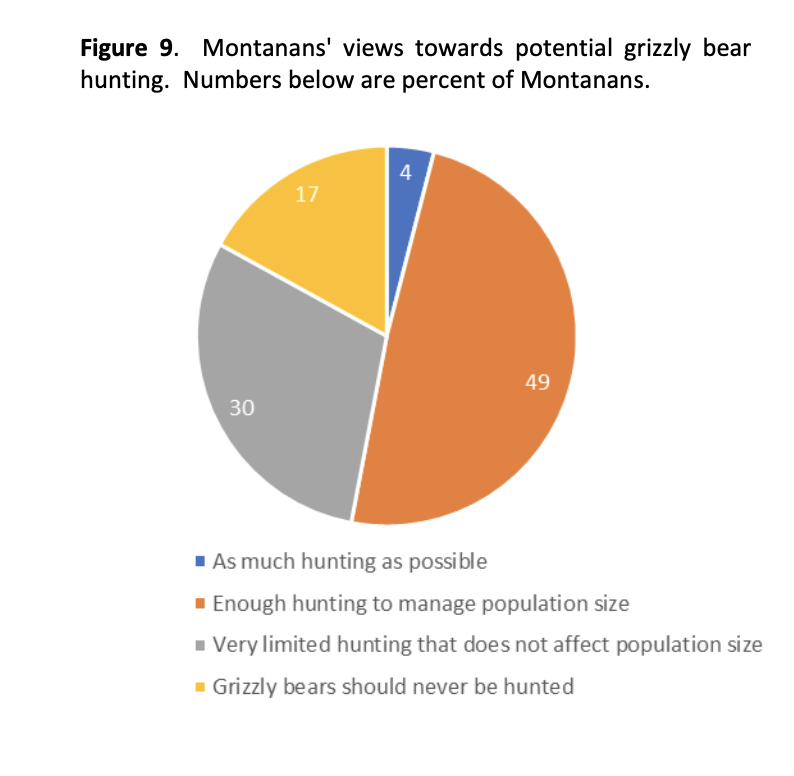

Hunting is one of the most controversial pieces of the plan. A 2020 survey found that 49% of Montanans support enough hunting to manage for a population target, while 17% said grizzlies should never be hunted. Tribes across Montana, including the Crow, Blackfeet, Northern Cheyenne and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, signed a 2018 letter opposing Wyoming’s proposal to establish a grizzly hunting season when the U.S. government last attempted to delist Yellowstone grizzlies. (That effort was ultimately blocked in federal court.)

Bradley also said she’d appreciate firm population targets, which the draft plan doesn’t include. Bradley acknowledged that putting defined population targets in writing would probably make FWP vulnerable to pushback, but said she personally would find reassurance in the certainty of a number.

“FWP does not outline how they will CONTROL the growing population, or at what point they will decide the landscape is full,” she wrote in her comments on the plan. “I need to know that we aren’t just going to let bears completely overrun the landscape, or expand into areas they don’t need to be.”

“There’s a carrying capacity and the biologists already know what that carrying capacity is, so it would be pretty easy for them to put a number on that,” she said.

‘BEARS ARE INCREDIBLY RESILIENT’

Prior to becoming the executive director of the Montana Outfitters and Guides Association in 2004, Mac Minard spent 22 years working as a fisheries biologist in Alaska, the only state with more grizzlies than Montana.

One day, while conducting research for his undergraduate degree in wildlife management and research, Minard counted 37 brown bears on a single Alaskan stream. (Though they’re technically the same species, wildlife managers consider grizzlies to be a smaller, inland subspecies of brown bear.) Two decades later, Minard’s colleagues at the Alaska Fish and Game Department participated in the state’s response to the deaths of Timothy Treadwell and Amie Hugenard. Treadwell, who’d written “Among Grizzlies: Living with Wild Bears in Alaska,” had been killed by the bears he’d been documenting for years. Minard also remembers an early 1990s incident when a female brown bear and her three cubs peered into his basement window as he watched TV with his daughter, who was about 2 at the time.

“I thought, well we can’t have that, so we go out and do some adverse conditioning,” he said. “[I went] out and put a load of bird shot in the bear’s butt and she decided this isn’t a place to hang out with her cubs.”

Adverse conditioning to discourage grizzlies from becoming too accustomed to human presence is one of the benefits Minard sees in hunting them. Helping wildlife managers reduce grizzly populations in places that exceed “sustainable biological objectives” is another, he said. He also said that, based on what he’s seen in Alaska, he anticipates public demand for grizzly hunts in Montana.

Minard, who now lives in Helena, said he has faith in the state’s ability to successfully and sustainably manage grizzlies, and generally supports natural resource management at the state, rather than federal, level. The federal government uses a “broad brush” in its management approach, he said, and is limited in its ability to take into account the multitude of values surrounding grizzlies.

“The federal management approach is only one way — it’s either on or it’s off,” he said. “With a state-managed solution, you look at a responsive commission to take into account the divergent social values that are placed on grizzlies and [tailor] regulations to accommodate those interests.”

“Bears are incredibly resilient,” Minard added. “I suspect that they are going to find a way to propagate and move around. They’re omnivores that can inhabit all kinds of different habitat types.”

Minard first spoke to MTFP a week before the federal government’s Feb. 3 announcement that it found sufficient merit in petitions submitted by Montana and Wyoming to delist NCDE and Yellowstone grizzlies. That announcement started a yearlong process for USFWS to explore the status of grizzly bears and the regulatory conditions in the three states — Montana, Wyoming and Idaho — that support grizzly populations.

It’s not the first time USFWS has pursued a delisting action: The agency attempted to delist Yellowstone grizzlies in 2017 but was blocked in federal court after environmental groups, the Crow Tribe and others sued to restore protections. The agency failed to account for how delisting of Yellowstone grizzlies would affect the recovery of other Northern Rockies grizzlies, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals found. The same court also blocked a 2007 Yellowstone grizzly delisting attempt, finding that evidence did not support the federal government’s conclusion that the loss of white bark pine (a food source for the bears and itself now a listed species) would not threaten grizzly recovery.

Minard alluded to that push-pull dynamic in his Jan. 31 conversation with MTFP. He said grizzly bear delisting is going to take time. It’s something he takes “a long view on,” he said.

“At some point, the political moon and sun and stars will align, the bear will be delisted and there will be some sort of hunting season established,” he said. “Life will go on and we will be able to chalk this up as a successful conservation effort.”

THE COEXISTENCE CHALLENGE

FWP wildlife division administrator Ken McDonald is one of the state employees tasked with balancing these divergent visions for grizzlies in the agency’s management plan.

Over the next month, FWP will wade through more than 600 comments that have been submitted by members of the public and government agencies, including USFWS. The department will issue a draft decision notice, which could include substantive changes to the plan that went out for public comment in December. The next iteration of the plan is a final decision notice. All told, McDonald said, he anticipates the agency will adopt a “final final” plan in April.

Grizzly bear hunting, one of the most controversial pieces of the plan, would still be subject to approval by the state Fish and Wildlife Commission, the seven-member, governor-appointed body that sets hunting seasons and decides where state wildlife managers can and cannot release captured bears. There is a public participation component to that process as well, McDonald said.

In response to criticism from conservation groups that mechanisms to support connectivity between existing grizzly populations are inadequate, McDonald said the plan gives FWP discretion to evaluate management of bears connecting the NCDE and Yellowstone regions on a “case-by-case basis.” There will be less tolerance under the plan for bears traveling east into the prairie that come into conflict with humans, he added.

“Bears are probably not going to be winners in those situations,” he said.

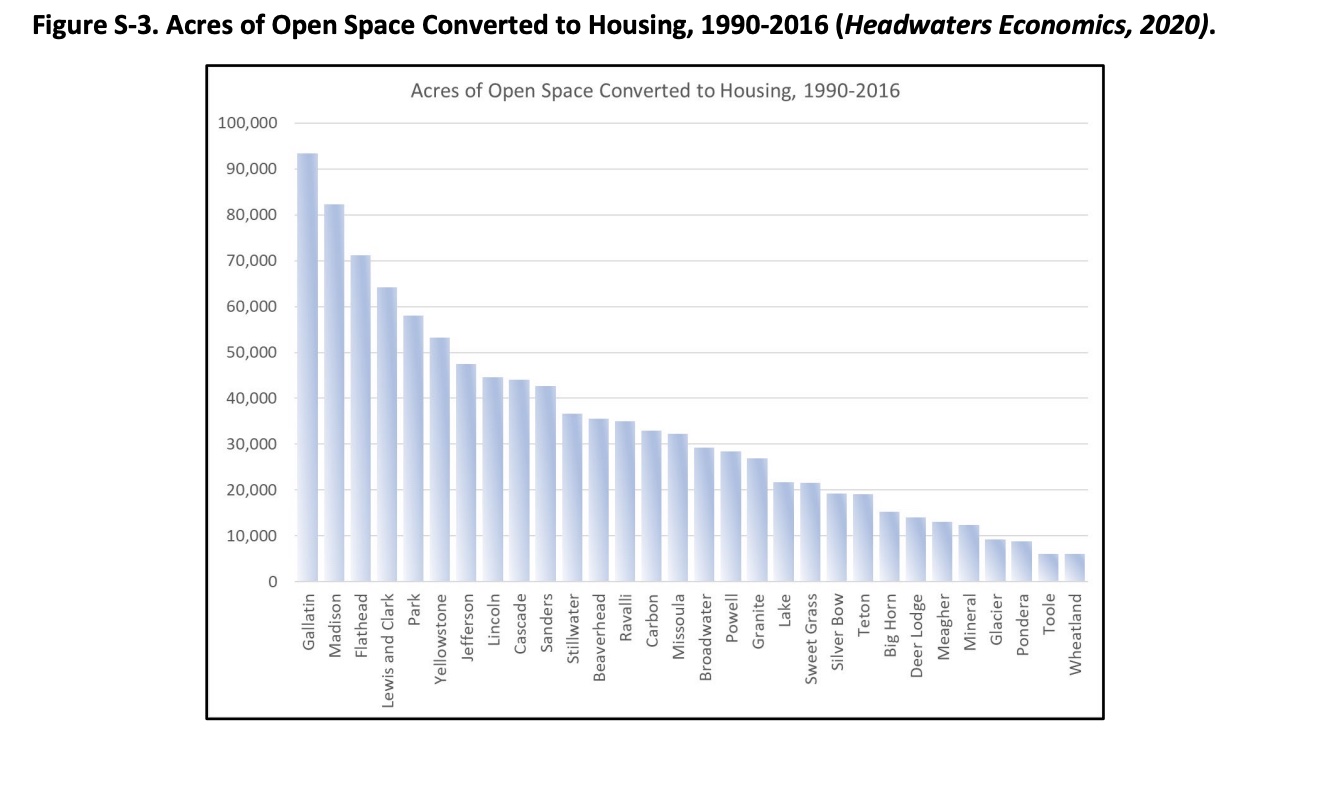

FWP is also grappling with the flip side of the expansion dynamic: human expansion into the wild, remote country that grizzlies favor. A 30-county region of western and central Montana that’s been identified as most impacted by the plan is home to 89% of the state’s human population, while accounting for only about half of its total land mass. More than a million acres of previously open space in that region — an area slightly larger than Glacier National Park — has been converted to residential development during this quarter-century, the state estimates.

FWP staff can comment on subdivision applications, but that’s where the department’s ability to influence land use on private property effectively ends, McDonald said. What the department can do, and has done, is hire more bear managers to prevent and mitigate conflicts, he said.

“Last fall, I had guys out in Gardiner for three days straight. Bears were coming into Gardiner at night, and the [bear managers] were trying to shoo them out of Gardiner so they weren’t there in the morning when people are out and about,” McDonald said. “Nobody really realizes the amount of effort and expertise that goes into helping bears and people live together.”

Like everyone else interviewed for this story, McDonald said grizzly management has become politicized. Constituents ask elected and appointed officials to set a different course, and those elected officials in turn urge wildlife managers to make changes. In the past decade, both Republican and Democratic politicians have called for state management of the state animal, including current Gov. Greg Gianforte, former Gov. Steve Bullock, and both of Montana’s current U.S. senators. FWP can curtail some of that politicization by minimizing conflicts between people and bears, McDonald said. It will help if people develop more tolerance for bears without feeling like they’re being unwillingly subjected to an overly restrictive regulatory framework, he added.

Asked what grizzly presence in Montana means to him personally, McDonald said he sees it as an affirming reflection of how the state has managed both bears and the habitat they rely on to thrive.

“To me the presence of grizzly bears is a symbol that Montana has enough — and big enough — wild places that critters like grizzly bears and other large carnivores can still thrive here,” he said.

Servheen, the retired USFWS bear biologist, said grizzly bears have a unique ability to heighten people’s awareness of the wild landscapes people share with them. Ask someone who’s had an encounter with one about the experience and they can often recall in great detail the events of that day, he said. They’ll tell you about the country they were in, what time of day it was, what the bear was doing and who they were with.

“All of this is burned into your memory, and that’s the magic of grizzly bears. They allow you to much more intensively experience the landscape,” he said.

Mike Madel, the FWP bear biologist who helped decide the fate of Grizzly 144, recalls with startling clarity the details of the windy November day in 2002 when he was asked to learn whether 144 had survived the shot delivered by a startled elk hunter. He remembers finding her prone at the bottom of a brushy hill she’d rolled down, her three cubs bawling, the sow eventually rising to her feet and the cubs converging to nurse.

Madel said his intervention was successful: 144 and her cubs hibernated and re-emerged in April. She returned to her usual denning ground the following year.

“As far as we know, she survived several more years,” he said.