By Todd Wilkinson EBS ENVIRONMENTAL COLUMNIST

Think about how language shapes the way we regard our relationship with the land.

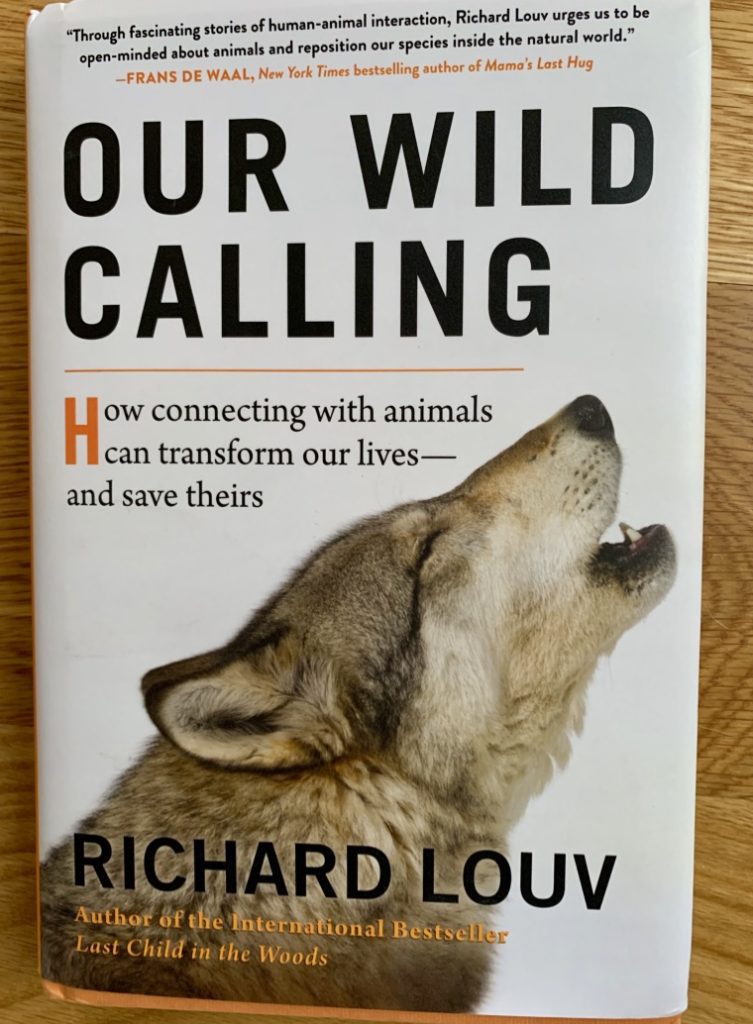

Richard Louv, the American writer who helped bring the term “nature-deficit disorder” into modern consciousness, has a brand-new book, this one focused on the benefits that come from humans sharing company and having interactions with animals.

“Our Wild Calling” is a journey of discovery, with Louv serving as interpreter, into the rapidly-growing body of scientific evidence showing how nonhuman beings possess not only intelligence but a range of emotions. As he notes, the most compelling proof comes from observing the dogs, cats, horses and other animals we share space with.

The book is an entertaining read that stays with you and prompts one to reconsider our own place in nature.

Louv, who is now on a national book tour and considers Greater Yellowstone one of his favorite regions, recently agreed to answer a few questions.

Todd Wilkinson: What are a few of the things you learned while doing research that previously you were unaware of?

Richard Louv: Research into animal communication within and between species is growing quickly. I learned that horses have more facial expressions than dogs, and are surprisingly similar to the signals that human faces send, but happen in micromovements difficult for most people to detect. Communication among animals is occurring around us all the time, in a kind of animal extranet. Male alligators attract females by emitting low-frequency sounds that bounce droplets of water on their backs. Try that on your next date. Birds do more than tweet.

TW: Elaborate on that.

RL: One of the people I profiled in the book is Jon Young, the founder of several nature connection programs, including 8 Shields and the Wilderness Awareness School in Duvall, Washington. He has taught hundreds of people how to communicate with, or at least understand, birds.

“Deep bird language,” as he defines it, refers to the specifics of bird life but is also about a different frame of mind and awareness. Humans and other animals have modes, gestures, sounds, bleeps and blurts—identifiable patterns that precede human language. Young has noted that people who learn bird language often apply what they have learned to how they communicate with their spouses, children or even their boss. And their lives improve. This is the Oldest Language, its origins older than most species living today.

TW: How do you think that having more empathy/sympathy for other life forms leads to a better society?

RL: One of the central themes in “Our Wild Calling” is the growth of human loneliness; they suggest that isolation is equal to or will soon exceed other risk factors for early death, such as obesity. I make the case that this loneliness is not only aggravated by anti-social media, but is rooted in a deeper species loneliness: a growing disconnect with the greater living family.

Research shows that the urban parks that have the best impact on human psychological health are the parks with the highest biodiversity, the widest array of animal and plant species. I don’t believe that’s an accident. As a species we are desperate to know that we are not alone in the universe. But intimacy is all around us. The number of dogs in the United States, proportionate to the human population, is higher than ever.

TW: Here’s a question related to your momentous book, “Last Child in the Woods,” and it has a link to this book: What do you think is the triggering mechanism by which a user of nature is converted or transformed into being a defender of nature and the other beings inhabiting it?

RL: One morning, during my own close encounter with two golden eagles on a lake shore, I became intensely aware of the reality that existed between them and me. Even if that reality existed in my imagination, what I sensed had meaning. I felt a change. I told this story to my son—this is the son who has the fishing gene; when he was three, I caught him fishing in the humidifier.

I told him: “Matthew, whoever I say I am, I’m not. Who I was in those moments is who I really am, and I don’t have the words to explain this.” In searching for those words, I came to this conclusion: We live in two natural habitats. One habitat is the physical environment that we work hard to protect from ourselves. The other is the habitat of the heart, which exists between us and other animals, including other humans. We often undervalue and fail to protect that second habitat. If one of those habitats dies, so does the other.

The human need to connect with other animals, and to find and express meaning through them, is baked deep within our psyches. Once, we told our stories around campfires. Physically acting out the experience, we became the bear. Now we do this around the electric campfire (YouTube) or, preferably, a dining room table, a front porch, a classroom. I’ll bet many of your readers have their own stories to tell.

Todd Wilkinson is the founder of Bozeman-based “Mountain Journal” and is a correspondent for “National Geographic.” He’s also the author of “Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek” about famous Jackson Hole grizzly bear 399.