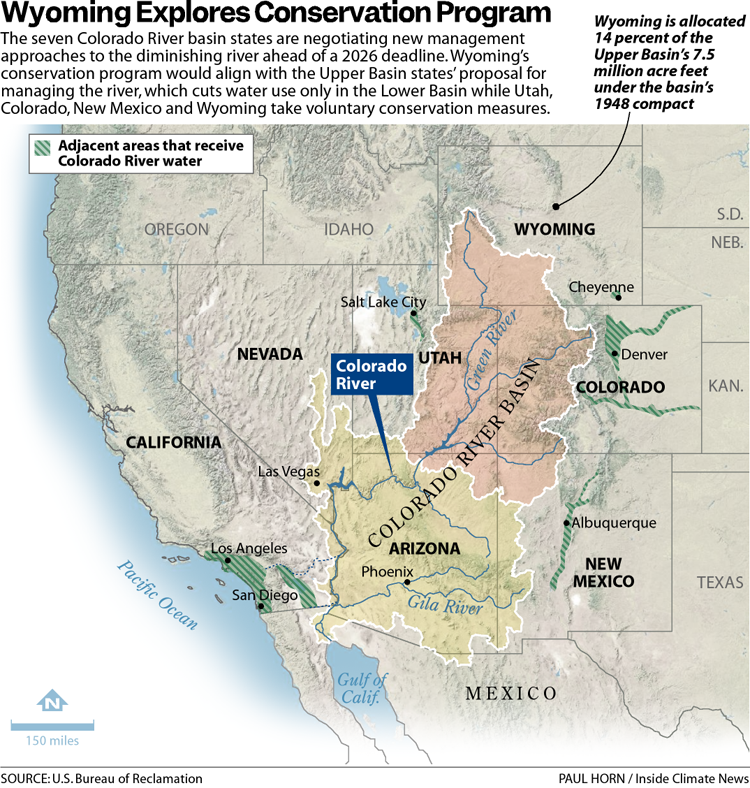

With Colorado River negotiations facing a 2026 deadline, the state wants to keep water management in its own hands, but lags its neighbors in planning to cut usage.

By Jake Bolster INSIDE CLIMATE NEWS

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

In Cheyenne, one of the northernmost cities receiving Colorado River water, the state engineer and attorney general’s offices met with legislators on the select water committee last month to discuss ongoing Colorado River negotiations. Their message was clear: Wyoming must adapt to a future in which the river has an inadequate supply of water for all of its users.

Brandon Gebhart, Wyoming’s state engineer responsible for managing and regulating the water within the state, and Chris Brown, with the Wyoming attorney general’s water and natural resources division, gave committee members background on the Colorado River negotiations, and outlined why it is in Wyoming’s interest to come up with its own water conservation statutes.

With many Colorado River basin mountain ranges holding less than 50% of their average spring snowpack, it’s clear that the river and its reservoirs will again be stressed this year by deepening drought.

“We don’t have anything set up right now,” Gebhart said. “But I think it’s very important that if we’re to do that, we need to do it in a way that doesn’t impact our water users, and it’s something that Wyoming can live with.”

Southwest Wyoming relies on water from the Green River, the Colorado River’s largest tributary, to feed agricultural operations, serve its towns and power its industries. But as climate change intensifies the decades-long drought in the West, and river users continue to demand more water than the system can provide, the Colorado River is running dangerously low, threatening the water supplies and livelihoods of 40 million people in seven U.S. states, 30 tribes and Mexico.

In an attempt to address river shortages and forecasted drought, the states and tribes have come up with new plans for how to manage the river ahead of an October 2026 deadline. Both the Upper Basin states — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — and the Lower Basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — have proposed cutting basin-wide use by as much as 3.9 million acre feet.

But, so far, the basins have been unable to agree on how to share those cuts.

The Upper Basin states have proposed levying the full 3.9 million acre feet of required cuts on the Lower Basin in proportion to elevation declines at Lake Mead, which serves only Lower Basin water users, while voluntarily cutting their own use. Under the Upper Basin plan, the Lower Basin would incrementally cut its water use once Lake Mead drops to 90% of its storage capacity; when the lake reaches 70% capacity, the cuts plateau at 1.5 million acre feet — enough water to cover 1.5 million acres with a foot of water. The cuts would remain at that level until Lake Mead dips below 20% capacity, at which point Lower Basin states cut water use by an additional 2.4 million acre feet.

The Lower Basin states have offered to cut their own consumption by 1.5 million acre feet, but only once the Lake Mead water level drops to 69% of its capacity. The remaining 2.4 million acre feet of cuts would be triggered once the system hit 23% capacity and be shared equally between the basins.

Gebhert, who is also Wyoming’s representative in Colorado River negotiations, told the committee a voluntary program of cuts is important in part because it underlines the viability of the Upper Basin states’ plan and shows the Lower Basin “the certainty that we can do something to contribute to the solution.”

It is unclear what a voluntary water conservation program in Wyoming would look like — except that it would have to accommodate several interests. Ranchers, in addition to having some of the most senior water rights in the Green River basin, draw the most water, and any voluntary conservation program would likely have to balance their needs alongside demand from the communities of Rock Springs and Green River, which together hold almost 6% of the Equality State’s population, and take into consideration industries like mining for trona, a mineral used in soda ash for glass, paper and detergent manufacturing. Mining companies make up a substantial portion of the region’s tax base.

There may not be consensus within each of those groups as to what shape a voluntary water conservation program ultimately takes.

“I hear everything from, ‘Well, we haven’t used our allocation of Colorado River water yet, why should we do anything?’ — which is a good position to have, but one I’m not sure withstands scrutiny in the overall federal picture [of the river] — to those who say, ‘Well, this may provide some opportunity for me to get some revenue from use of some of my water,’” said Jim Magagna, executive vice president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, a ranching trade group.

Magagna hopes that as the state engineer’s office drafts its pilot program, it will account for the impacts of voluntary cutbacks of water use on landscapes and ecosystems that have historically been irrigated at a certain time, in a certain way with certain quantities. The state engineer’s office’s pilot program would likely affect urban and industrial water users in the Green River basin, not just agricultural users.

“I really appreciate the fact that they understand the need to involve everyone,” Magagna said.

Wyoming is, in the estimation of Chris Brown, a senior assistant attorney general, behind its peers in the Upper Basin — particularly New Mexico and Utah — in developing a voluntary water conservation program, he told state legislators.

In 2023, the Utah legislature passed a bill requiring water conservancy districts and water utilities over a certain size to submit conservation plans and update them every five years. They have access to state loans or funding to improve water uses. New Mexico makes water conservation resources available to homeowners, industrial users, landscapers and public utilities, among others.

The meeting concluded with members of the select water committee authorizing the state engineer’s office to come up with draft legislation for a pilot conservation program. Lawmakers plan to review that draft during their next meeting in August, at a yet-to-be-determined location.